A subway system in Detroit? Here are 6 times the city tried — and failed

For rail-based public transit, Detroiters today have two options — the People Mover and the QLINE — each with well-known shortcomings.

The city's last streetcar went offline back in the 1950s. A fleet of novelty downtown trolleys ended service in 2003.

Yet at several points in history, Detroit came somewhat close to getting a real subway system. What thwarted each plan in the end was a lack of money, lack of political will or sometimes both.

Knowing how Detroit went on to experience steep drops in population, one might consider the failure of each push as not necessarily a bad thing in hindsight. Detroit has had plenty of financial problems — but keeping an empty subway running isn't one.

Yet speculation can also go the other way. Perhaps a Chicago-style subway with some elevated lines and light rail would have unlocked an alternative course of history for Detroit, one in which it retained more population and urban density in the latter half of the 20th century and stayed a top 5 U.S. city.

"It would have been a game changer," said Michael Boettcher, an urban planner and historic Detroit tour guide. “I think had any of those been built, that would have been something that could have kept more people. We would have fallen in population; we still would have lost the industrial jobs and that kind of thing — but who knows."

At the very least, he added, "it could have kept economic activity around the stations. You look at any modern city today, and where the subway system is, where the rail system is, is where the density is.”

Here are key moments in the histories of Detroit's unbuilt subways.

A mayor's 1920 veto

There was a proposal in 1920 to construct dozens of miles of subway lines and elevated rail lines across Detroit. It followed an earlier 1915 report on the feasibility of a Detroit subway.

But the new proposal called for a public-private partnership with a private firm that had a monopoly on Detroit streetcar operations, known as the Detroit United Railway, or DUR, and that drew opposition from Detroit Mayor James Couzens, a DUR critic.

Couzens told the city's newspapers that he thought Detroit was still too small for a subway, and wouldn't need one until it had at least 2 million people. (Detroit's 1920 population was just under 1 million.) Couzens vetoed the transportation plan and an attempt by the city's Common Council to override the veto fell short by one vote, according to DetroitTransitHistory.info.

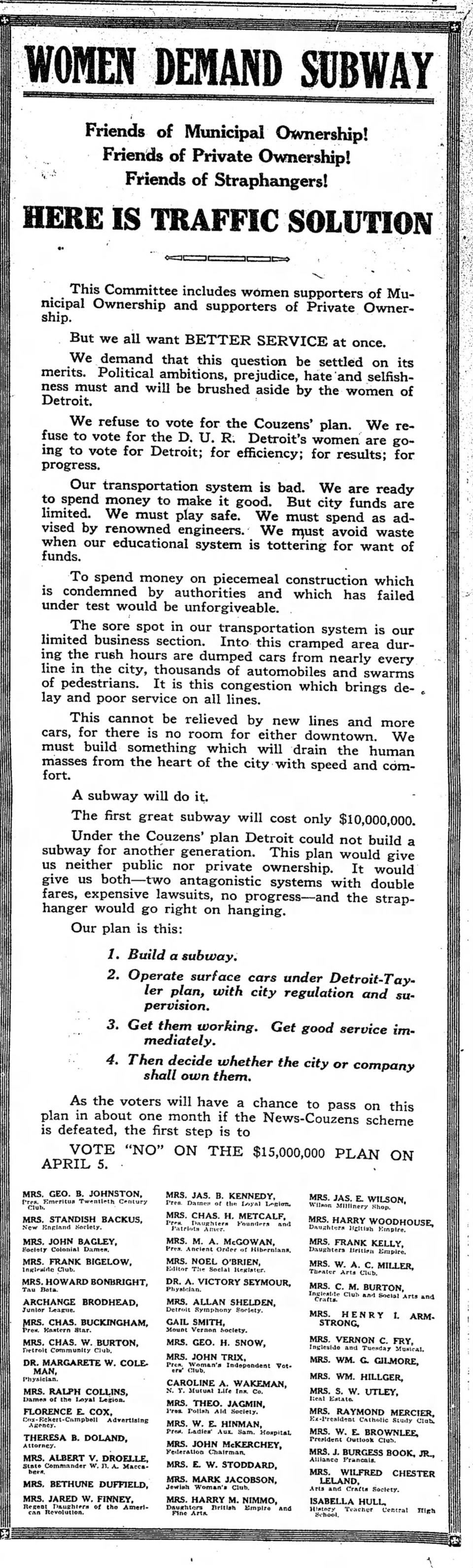

A 1927 near vote

Subway advocates brought forth another plan in 1927 that envisioned an extensive 21-mile system, with lines running out Woodward, Grand River and Gratiot. The project's reported $135 million in costs was to be financed through bonds, city funds and a special assessment on abutting property.

The plan was to be presented to voters in April 1927. Official election notices were even printed in newspapers.

But Detroit Mayor John W. Smith requested at the last moment that it be taken off the ballot. According to Free Press archives, the mayor's professed reason was that Ford Motor Co. was making model changes and it was a bad time to pose the question when there was a considerable number of laid-off workers.

Yet a likely greater influence on the mayor, according to the Free Press, was opposition by big taxpayers who didn't like the special assessment idea.

The 1929 failed vote

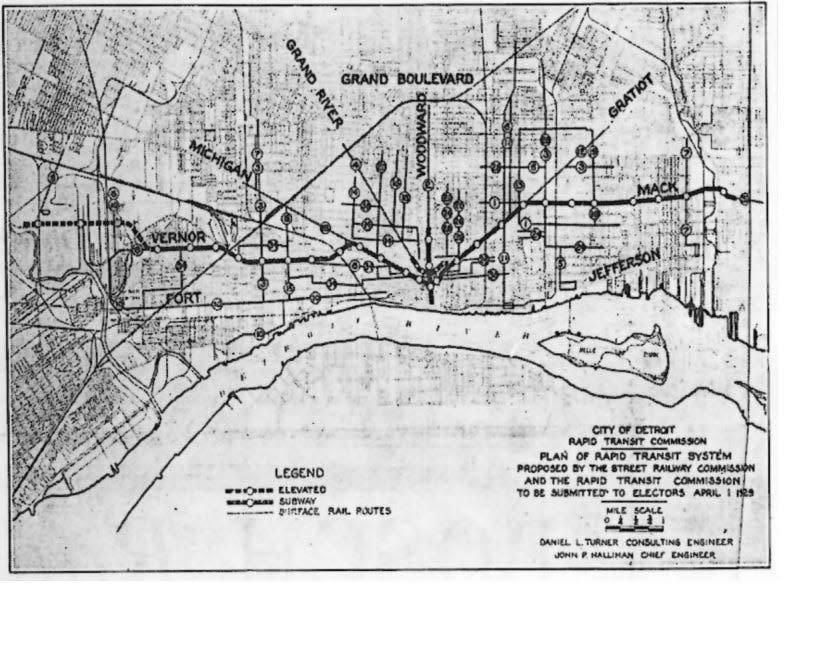

The subway plan was revised and downscaled. The reworked plan was less costly at $54 million, and still included downtown subway lines that would transition to elevated tracks radiating out along Woodward, Gratiot, Grand River, Michigan, Vernor and Mack avenues.

One subway line was to begin near downtown's Campus Martius and become an elevated line, extending all the way out to Ford's River Rouge plant, according to a detailed map that ran in The Detroit Jewish Chronicle. The plan also called for various below-grade roadways in downtown for vehicle travel.

All of it was to be paid for with higher taxes and city bond issues.

However, Detroiters resoundingly rejected the plan in April 1929, with 72% voting against it and just 28% for it.

One nay voter explained their reasoning in a Free Press letter to the editor, declaring that subways were obsolete in the age of mass car ownership.

"My idea is that subways went out when automobiles came in," wrote T.C. Hughes of 2615 Joy Road. "Subways were designed and built before the automobile was ever thought of and along with narrow streets have in this day proven unwise."

Other commentators faulted big-taxpayer opposition again for the plan's demise.

Voters like 1933 plan, but then ...

Another reworked proposal, this time in 1933 during the depths of the Great Depression, was later said to be the closest that Detroit ever got to a subway.

This $88 million plan called for building about 20 miles of subway and elevated rail lines, starting in downtown and extending out to Dearborn and Highland Park. The project was to be paid for through government bonds and future subway fare revenues — no local tax increases or assessments — and supporters expected to get crucial federal assistance from the New Dealers in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration.

Detroit Mayor Frank Couzens — the son of former Mayor James Couzens — was onboard with the plan. He hoped it would create jobs for 9,000 men and indirectly 24,000 more.

This time, Detroit voters in November 1933 went for the plan, with 68% in favor.

For a short while, it seemed like a subway was really going to be built. Until suddenly it didn't.

In March 1934, the head of Roosevelt's Public Works Administration, Harold Ickes, made it clear that the government wasn't going to fund a subway for Detroit — and especially not if the city itself wasn't pitching in money of its own.

"Detroit very graciously asked the federal government to build it a subway system; asked us to proceed with a project in which Detroit itself had no confidence," Ickes said.

Rather than mourn this news, the Free Press editorial board applauded.

"The Detroit subway scheme was, in short, a piece of mild insanity, and Secretary Ickes has done this town a service by clearly ending the business."

Scaled-down 1941 proposal

A further scaled-down plan for a subway was championed in 1941 by Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries. The $39 million project was to extend 8.8 miles along Woodward Avenue from downtown to the State Fairgrounds.

Ten car trains were to operate on the line, with feeder bus service going to the 19 subway passenger stations, according to an article in the now-defunct Detroit Evening Times.

Jeffries made the proposal in July 1941, a time when World War II was raging in Europe but before the United States was involved. That same week, the head of Detroit's public works department was visiting London — recently under siege by Adolf Hitler's air force — to report on the usefulness of subways as air raid shelters in the event of war.

Detroit's subway plan soon fell off the radar following Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into the war.

Near the end of the war, Jeffries came back to the subway idea as part of an overall transit plan for the city. Consultants devised a 1945 plan that envisioned subway lines along Woodward and Grand River. But it didn't happen.

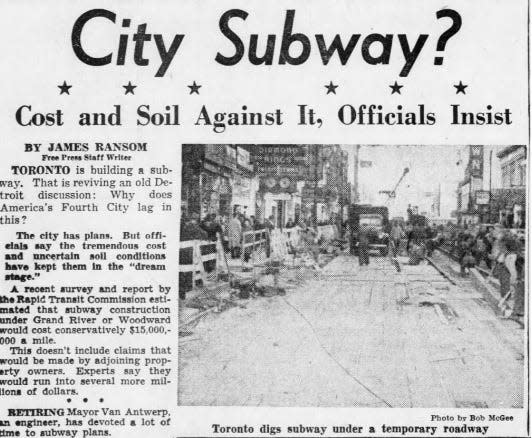

Later on, some questioned whether the Detroit soil would even allow for underground rail lines.

"Soil conditions in almost all parts of Detroit would make a subway very difficult to construct," Detroit Mayor Eugene Van Antwerp, who opposed an idea for a 1.6-mile downtown subway, said in 1949. "The blue clay under the surface is a jelly-like substance that shifts easily."

Ford pledges $600M check

Many of today's Detroiters were alive during for last serious push for a subway.

It began in 1976, two weeks before a November election that pitted President Gerald Ford, a Republican, against Democrat Jimmy Carter.

In what political observers considered an attempt by Ford to shore up support in his home state, Transportation Secretary Bill Coleman came to Detroit and handed a $600 million mock check to Mayor Coleman Young for the stated purpose of building a subway system. (That $600 million would be around $3 billion today.)

Young, who a year earlier had approached the Ford administration about such a system, originally envisioned a 20-mile, V-shaped subway beneath Woodward and Gratiot avenues.

But Detroit didn't have full control over the pledged federal money. (The $600 million also was to entail a $150 million state match.)

The subway plan needed approval from suburban leaders through what was then the Southeastern Michigan Transportation Authority or SEMTA, the precursor to today's Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation.

And SEMTA wasn't onboard.

There was nasty squabbling for several years between Young and suburban critics who argued that a subway was unnecessary, too costly and would siphon a disproportionate share of federal and state transit dollars — leaving little for the suburbs.

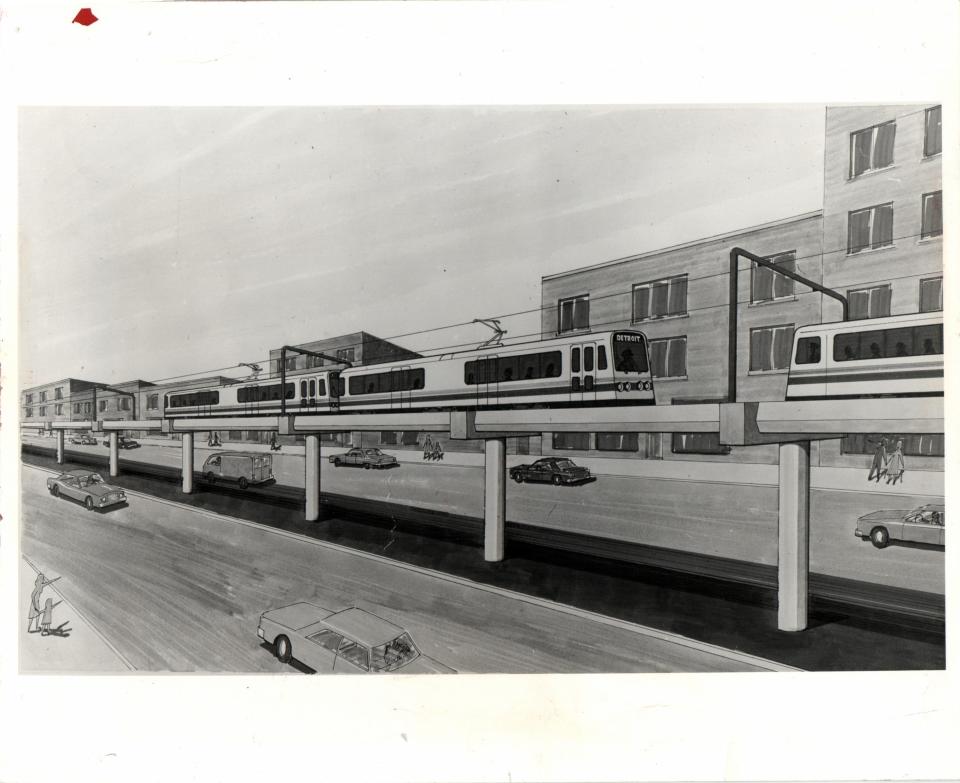

By 1980, Young's subway plan had evolved into a more comprehensive Woodward Corridor subway-rail line system. It called for an underground subway to be built from downtown to New Center, where it would transition into an elevated rail line running to McNichols (Six Mile). From there, a new light rail system would take over and extend beyond Detroit and into Royal Oak, and possibly later into Pontiac.

Total costs were forecast at $1.5 billion, with $1.1 billion for just the subway piece.

The plan was very controversial. The majority of callers in a February 1980 Free Press readers poll said they didn't think a subway should be built in Detroit.

"A Woodward subway will need only two stops, one at RenCen and the other at nowhere," said one cranky respondent.

Reagan yanks $600M check

Momentum petered out once President Ronald Reagan replaced Carter in the White House. The new Republican administration undertook cuts to mass transit subsidies and most future projects.

Soon it was official: The $600 million federal pledge was dead, as was any path forward for a Detroit subway.

But there was a silver lining. Some federal money was still available to build the Detroit People Mover, and its 2.9-mile elevated downtown loop officially opened in July 1987.

The late Bob Berg, who was Young's press secretary, recalled in a 2017 Free Press interview how the mayor never intended the People Mover to be a stand-alone system like it is today. Rather, it was envisioned as the terminus for a never-built regional light rail system — similar to what Young envisioned for his unbuilt subway.

"The thought was, ‘We’re better off to have that than nothing,’ ” Berg said.

Contact JC Reindl: 313-222-6631 or jcreindl@freepress.com. Follow him on X @jcreindl.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: 6 times Detroit tried to get a subway system — and failed