'The Thing' at 40: The cast & crew's definitive history of John Carpenter's masterpiece

"The ultimate in alien terror" was a mere promotional tagline in 1982. Today, those five simple words refer to one of the greatest (if not the greatest) science fiction horror movies ever made (now streaming on Peacock). It's hard to believe that 40 years have passed since the release of John Carpenter's The Thing, which blended elements from 1951's The Thing from Another World and the John W. Campbell Jr. novella it was based on, Who Goes There?, to form an entirely new specimen that has been nigh-impossible to imitate all these years later.

Carpenter's affinity for the material was evident in 1978's Halloween, which featured a scene where Laurie Strode and Tommy Doyle watch the Howard Hawks-produced Thing from Another World on television just before Michael Myers' murderous rampage throughout the neighborhood. That little homage might have remained the director's only connection to the property, had it not been for his old buddy from USC film school, producer Stuart Cohen, who convinced him to take on the project.

"It was not something I wanted to do," Carpenter tells SYFY WIRE. Universal had [the rights to] The Thing and they wanted to remake it. The original Thing [from Another World] was one of my favorite movies. I really didn't want to get near it. But I re-read the novella and I thought, 'You know, this is a pretty good story here. We get the right writer, the right situation, we could do something [with this]. So I decided to do that. This was right after Escape from New York. I had my first studio movie, which was a big deal."

The "right writer" turned out to be Bill Lancaster, son of Golden Age Hollywood star, Burt Lancaster.

The Effects

A tale of snowy isolation and creeping paranoia, The Thing follows a group of 12 men at an Antarctic research station who find themselves besieged by a thawed-out alien life-form capable of replicating any living organism. It wants to take them over and head for more populated areas until the whole world is absorbed.

"We went back to the origin of the story, which is the imitation," Carpenter says. "It wasn't a big Frankenstein monster, it was a creature that can imitate other life-forms perfectly. It's a lot more complex and different than the first film."

The slow erosion of trust between the characters leads to in-fighting and violence as the alien, which can only be eliminated with fire, begins to pick them off — all while assuming a number of gruesome forms it has learned to mimic from a lifetime spent traversing the universe. This utilization of a frozen locale and horrific extra-terrestrial being of unfathomable origin may conjure up the cosmic dread of At the Mountains of Madness (published two years before Who Goes There?). However, Carpenter insists that the literary works of H.P. Lovecraft were "not really" on his mind while making The Thing.

The effectiveness of the titular creature comes down to the incomparable work of Mr. Rob Bottin, whose trailblazing (not to mention nightmarish) creature designs set a new benchmark for practical effects. "He said, 'Well, the Thing can look like anything.' I thought about it and [came to the conclusion of], 'Well, that's true because it's been throughout the universe. Whatever's it imitated, it can pull it up,'" the director explains. "So why have one Thing? It's a constantly changing creature."

Bottin put in so much effort on this film, that he was briefly hospitalized for exhaustion. "He worked a little too hard sometimes, I'm afraid," Carpenter adds.

The director's favorite alien design is the Norris head that splits away from the man's body (like a TGI Friday's patron pulling apart a fresh mozzarella stick) during the iconic defibrillator sequence with Dr. Copper. "The most fun was the head coming off and sprouting legs and crawling away. It was ridiculous, that's why. At this point, the creature was designed after the script [was written]. I read Bill Lancaster's description of this scene and he came up with the line, 'You gotta be f— kidding,' which I just think is perfect."

More on that scene later...

Despite the fact that his adaptation would be vastly different from the 1951 version, Carpenter still wanted to pay homage to the OG movie by recreating its famous opening title sequence, in which the letters seem to burn right through the screen. Not only would it serve as a love letter to one of his favorite movies, it would also hint at the brutal method through which the Thing takes over its victims by tearing through their clothes.

Bottin, who had just finished up work on Joe Dante's The Howling, suggested Peter Kuran of VCE Films for the job. A veteran of the first Star Wars and the Battlestar Galactica TV series, Kuran landed the gig by bidding $20,000, which was significantly less than the price tag proposed by Roger Corman's New World Pictures. Had Corman's company won the contract, The Thing's opening title would have been handled by an up-and-coming James Cameron. "I [can] actually say that I beat him out on a job," says Kuran, who accomplished the title effect with a number of everyday items: a fish tank, a garbage bag, and some matches.

"I eventually [landed on] a setup that had a huge fish tank, which I used to put smoke into. Behind that, I had a frame that I stretched garbage bag plastic over. And behind that, there ... a 1000-watt light being held back by the garbage bag plastic because [it] was opaque black. I put the title on the back of the fish tank using animation black ink in the cel to make the title. When I'd start the camera, I'd run behind and touch the garbage bag plastic with a couple of matches. The matches would make a hole, they would burn and open up and reveal the light, which then came through the title [making] the rays in the fish tank. We did several takes and got the one that we wound up using. One of the takes opened up and just said 'NG.' It didn't open up all the way."

Kuran's decision to use a fish tank was the result of a rather disastrous experience on The Wrath of Khan, which hit theaters the same year as The Thing. "I'd done a shot on Star Trek II [where] I used a salt heater and sugar to put together this effect. I did it inside and it just completely smoked out the whole building. So I learned from that and when I did The Thing, I put it in a tank, so that the smoke was in a tank [and] it wouldn't go anywhere further than the tank."

The Thing's opening titles also feature a nod to the wider culture of 1950s sci-fi in the form of a flying saucer that crashes to Earth hundreds of thousands of years before the events of the movie. The ship was actually a miniature model constructed by Susan Frank née Turner. "[Peter] sent me over to speak with John Carpenter by myself and it was great," she recalls over the phone. "Carpenter told me his concept of what a spaceship should be like — he liked the '50s spaceships. He was very nice person, very cordial [and] very supportive. So I went back, and I made it."

She continues: "We used motion control to film the spaceship in the opening sequence of The Thing, using different passes for the shots. One pass was the ship itself; two was the chasing lights on the perimeter of the ship; three was for the stationery lights. These different pieces of film were expertly combined by Pete Kuran in the optical printer with the matte painting of Earth by Jim Danforth and the 'exhaust flame' cel animation I created."

Turner still has the UFO model in her possession and hopes to sell it over the next couple of years.

The Thing (1982) Artwork Still Photo: copyright Susan Turner

The Cast

With the creature designs and title sequence squared away, Carpenter set about finding his crew of frost-bitten men to populate U.S. Outpost #31:

Kurt Russell (helicopter pilot, MacReady), Keith David (mechanic, Childs), David Clennon (mechanic, Palmer), Richard Masur (dog handler, Clark), Joel Polis (biologist, Fuchs), Peter Maloney (meteorologist, Bennings) Donald Moffat (station chief, Garry), Wilford Brimley (biologist, Blair), T.K. Carter (cook, Nauls), Richard Dysart (physician, Dr. Copper), Charles Hallahan (geologist, Norris), and Thomas G. Waites (radio operator, Windows).

Some of the cast (like Dysart and Hallahan) were already established Hollywood veterans while others (like David, Waites, and Polis) were promising young graduates of Juilliard and USC. "Everybody had a character that they would play, but [it felt] natural and fit together," Carpenter says. "I'm very happy with the cast."

Clennon credits Lancaster with building such memorable protagonists in the screenplay: "He created these characters and gave them dialogue. I think that's why I wanted to do the film because I sensed on my first reading that the way these 12 men interacted, he had sort of elevated the form. I'm talking like a snooty pooty pretentious literary critic of horror films. But I thought he had done a really fine job of bringing these 12 people to life."

Maloney recalls his audition at the now-defunct Coca-Cola Building once located along New York's Fifth Avenue: "I went up there with a whole bunch of other guys [actors who were not ultimately cast] ... John led us in improvisation. We teamed up, turned the tables over, and threw things back and forth across the room, pretending that we were at war with this monster, which was, of course, not there. That a fun audition."

Clennon was originally up for the role of Bennings "because they thought I could play a scientist," the actor says. "I look like a kind of nerdy, science guy. I got a lot of that [back then] and I said, ‘Yeah, okay, I'll go in.’ I guess I read the script, and thought, ‘Okay, I don't like I don't like horror films. I don't go to horror films. I'm too delicate. But there’s something about this script is fairly interesting and oh yes, it's based on a classic sci-fi [novella] that gives it a little literary class. So, yeah, I'll go in. But I also want to read for the part of Palmer because I think I could do something with it, even though it's against type.’"

He whole-heartedly agrees with our characterization of Palmer as a stoner, slacker, and conspiracy theorist rolled into one tight little package — not unlike the joints Clennon taught himself to roll for the movie. "The big spliff was my idea. And in another scene, I was smoking from a little pot pipe. I had a little folding wooden pot pipe that I owned and used in real life, so I was using that on the set ... You brought up conspiracy theory [and] I would never have used that term to describe what goes on in Palmer's head. But you're right, that is a way of categorizing it. It’s a fantasy, it's Chariots of the Gods, it's an explanation of why the world is as it is in his mind. But you're right, it’s a cousin of conspiracy theory. It's just such a great element."

Masur states that he was first interested in the role of Garry, but ended up choosing Clark after reading the script. "I said, 'The thing that I'm most attracted to is the dog handler.' [John] said, 'Really?' I said, 'Yeah, I love this character. I just think he's so misanthropic. He doesn't seem to want to be with anybody, but the dogs.' He said, 'Well, it's yours, if you want it.' And that was it."

To prepare for the role of Fuchs, Polis approached his character by enrolling in a beginners biology class at Baruch College in New York. "We dissected a frog and I just got into it."

David, meanwhile, saw Childs as "the strong, silent type. He was a man a few words, he didn't say a whole lot. But when he did, it counted. I just took took him as being [a person] who observes and notices everything at least twice."

A method actor by nature, Waites went pretty deep on the character Windows (originally called "Santiago" in the screenplay), which drew a bit of teasing from his fellow co-stars. "Kurt and Wil Brimely — God rest his blessed soul — used to make fun of me and say, 'What are you guys doing? Discussing your motivation?'"

He continues: "I was trying to find something about the guy, who he was and what his dreams were. Did he want to work in a f—ing radio station in the Arctic for the rest of his life? No, he had to want to be something else. So I have him reading — I know this is very subtle — a Hollywood magazine with pictures of famous movie stars from the time on the cover. Because that's what he wants to be doing; to be in the movie business and be a movie star. And movie stars wear sunglasses. I picked up a pair of green sunglasses in Venice [California]. I was wearing them [when] I came into rehearsal, I kept them on, I read the character, and I went up to John on the break. I said, 'John, from now, from now on, I want everyone to call me Windows.' He looked down at the floor, and he looked up at the ceiling and took a long drag on the cigarette and put the cigarette out. You could see him thinking it through and he went, 'Alright, everyone! From now on, Tommy wants everyone to call him Windows, okay?'"

This apparently drew some backlash from Moffat and Clennon: "They're like, ‘This is f—ing bullsh**, man! This is so arbitrary! What are you doing, letting him call himself Windows and wear sunglasses inside?!’ John…I don't think he gave a f— what they said. I think they only said it to me. I think they ridiculed me because they thought I was just doing it to get attention. But I really wasn't."

"Donald Moffat ... didn't want Tommy Waites to wear those sunglasses through the whole movie and he didn't want to have to call him Windows," echoes Maloney. "That was a last-minute change around the table. Tommy said, ‘I think my character wears sunglasses all the time and should be called Windows.’ John said, ‘Okay!’ And Bill Lancaster, who was with us there during those weeks, said, ‘Okay!’"

A fun little aside: The Thing features a pair of characters named "Mac" and "Windows" long before the advent of personal computers.

Credit: Universal Pictures

Before production began in earnest, Carpenter insisted on two full weeks of rehearsals (a highly unusual occurrence on a big-budget studio movie like The Thing), which took place on an empty Universal soundstage. "It was just having the actors get comfortable with their roles and with each other," the director says. "It was very, very valuable. There really wasn't wasn't much more than, 'Let's go through this, fellas.' They worked out a couple things and they worked out their characters."

"We really established relationships with each other and I think that comes through in the film," adds Polis. "When we finished filming the film, John famously said, 'I'll never rehearse actors again.' But 40 years later, I'm told — I don't know if it's true — but I think he thinks it was his best film. And I'm sure it's because of the relationships."

"[We'd] take the time to talk about the script and offer ideas [and] those of us who would like to do research did research, brought it in and shared it with everyone," Maloney remembers. "Then we wrote things on the on the board, we learned a lot about what it's like to be in the Antarctic."

Clennon states that the rehearsal period was marked by a number of "metaphysical" conversations about, 'Do you know, when you have become the Thing?’ and stuff like that. I thought, ‘It doesn't matter. We're making a movie.’ What matters is that the audience doesn't know who’s the Thing. To speculate about whether Palmer knows he's the Thing after he's been absorbed by The Thing and how that’s going to affect his acting is metaphysical bullsh**."

During this period, Masur spent a lot of time with the dog — a half-wolf mix named Jed and trained by a man named Clint Rowe — that gets chased to U.S. Outpost #31 by the Norwegian helicopter. "Jed was just remarkable," says Masur, who practiced with the canine for hours until the two could walk "in this totally casual way" down the hall leading to the kennel. "I love dogs," he adds. "I always have." Shortly after the lights go down, the seemingly docile animal reveals its true nature and begins assimilating the other dogs, prompting Childs to burn it with a flamethrower.

"Everybody always thinks it's so sexy and exciting. It was scary," David admits of wielding the flamethrower prop. "It wasn't napalm, but it was real gasoline coming through a real pump and a real gun and [producing] real fire. A slip of the finger could cost somebody their life or certainly lots and lots of damage. So, it was a little scary. I was excited and glad to be doing it, but it was a little scary."

Maloney, who had a terrible fear of dogs at the time, also needed to spend time with Jed in order to feel comfortable enough to let the dog jump up and try to lick his face near the start of the film. "When Jed stood up and put his paws on my shoulder and licked my face, he was taller than me, I think. I was pretty freaked out by having to do that."

Clark's hunting knife, which makes an appearance during the scene in which Garry cedes command to MacReady, was Masur's idea. He went to pick it up on one of his lunch breaks and accidentally cut his thumb:

"It just started bleeding like a stuck pig. I was in my costume and I take my hat off and I I'm holding it against my thumb. I drive like this over to this emergency room, which was not too far away. I walk in, I'm sitting and I'm like, ‘I have to have somebody look at this right now. I gotta get back to work.’ And they said, ‘Well, you gotta wait’ and I said, ‘I’m bleeding like a pig here!’ So the guy looked at it, he put about a butterfly [bandage] on it — it didn't need a stitch — and he got it to stop bleeding. I went back to work and forget what I told wardrobe. I [I think I] told them I dropped it in a puddle or something [like that] because it had blood on it, but it was dark cap, so you couldn't really see it."

Principal Photography

Once rehearsals were over, the shoot commenced, with Carpenter's trusty cinematographer — the legendary Dean Cundey — back at his side after Halloween, The Fog, and Escape from New York. The key to this movie, Cundey tells SYFY WIRE, was finding a sense of realism.

"We didn't remove walls from the set so we could back the camera up and get wider shots. We shot everything as if we were actually there and I think that gave a sense of reality to the environment," he says. "I made sure that the lighting came from the practical lights that hung overhead in the set ... I also think it was because the creature, in its various forms, was on the set. It was not a tennis ball on a stick, as so often it is nowadays. It was, in fact, something the actors could see, touch, feel. I think all of those authentic touches created an atmosphere — not only for the actors, but also for the crew."

The biggest challenge was shooting Bottin's creations in such a way that they felt alive and took "advantage of textures and gooey slime and all of the stuff that we used to give a sense of weirdness to the creature," the DP explains. "So it was all carefully done. Rob [would] set up the creature, would point and say, 'Okay, I hate this area, let's not look at that too much. This [area] came out okay.' And so, I would very carefully light with little little pools of light and darkness for the creatures that he built in an effort to show off their best aspects, their strengths — rather than the audience looking at something too big. And saying, 'Oh, well, that looks like a blob of rubber to me.'"

x"We are the last of the great rubber movies," Masur says. "After us, things started going pretty much all CGI for these kinds of effects. But Rob Bottin got to do the Mona Lisa/Sistine Chapel of rubber. And it's pretty impressive, I gotta say."

"It's an important film for being one of the last films that was made with all the old techniques," echoes Turner.

"We didn't go to computers because they didn't really have them back then," Carpenter concludes. "They didn’t have it perfected and I'm happy with the way it looks. It's fine as it is. I don't see why you’d change anything."

On the Set of "The Thing" (Photo by Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images)

Filming mainly took place on Universal soundstages that were constantly kept between 40-45 degrees in an effort to simulate the Antarctic setting. "It was cold in there and so, I had the costume designer make a woolen neck warmer, which I wore in the movie," Polis reveals. "And in in a week's time, the whole crew was wearing neck warmers."

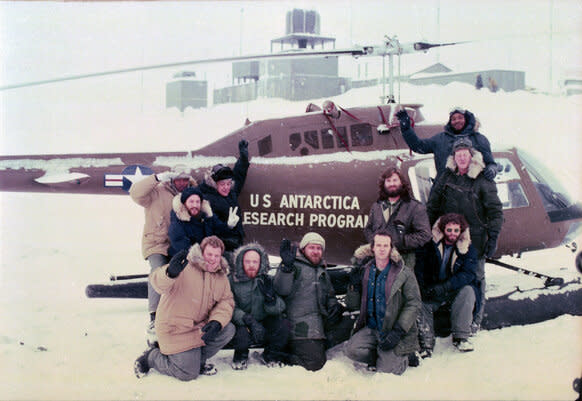

Exteriors were filmed on the Salmon Glacier up in Stewart, British Columbia (near the Alaskan border), where a life-sized research station was erected. The crew then allowed the snow to accumulate for several months before making the journey north. "One of the things that fascinated me the most was how they made the set in [Canada] look exactly like the set that we were on in Universal," David says." I mean, the same pictures hung the same way. It was as if they had lifted that room and put it in [Canada]."

It was a breathtaking spot, but the weather never stayed consistent. White-outs, overcast skies, and below-freezing temperatures never failed to wreak havoc, especially with regards to the cinematography.

"Once you get a cloud or clouds overhead, then everything goes white. And we had to match the skies, which were clear and beautiful, so it was a pain," Carpenter says. "It was a mountain that we had to go up. We were down by the bottom of the mountain and then we had to travel up every day. We'd get up there, the weather would be sh**, we'd have to wait all day long, get nothing done, and then go all the way back down ... We all were in it together. It was not an easy film to make. We had to fight the elements. It was rough. And since we were all in it together, we all bonded. Everybody bonded."

"I've backpacked all over the United States and so, I love the outdoors. I was in heaven. It was an adventure," Polis adds. "T.K. Carter hated it. He was used to LA, he had never been in that kind of cold. And some other people didn't like it very much. But man, it was so beautiful up there and we had all these great toys: helicopters, flame-throwers, and all this sh**. It was like a kid's dream come true."

At the end of many rough, yet rewarding, work days, the gang would unwind in the Alaskan town of Hyder with plenty of free-flowing Everclear to keep them warm. "That became a hazing or a ritual that we put ourselves through," continues Waites, who has since become a recovered alcoholic. "We did a lot of drinking and a lot of partying. It was burning the candle at both ends — staying up all night and having to shoot all day. It was the ‘80s, man. It was a different time."

Of course, not everyone got in on the merriment. "Donald was a family man and [became] upset when we would come in at three in the morning drunk from the bar and wake him up," states Polis. "But he was a good man, and a wonderful actor."

Despite the uncooperative climate, Carpenter wanted to make full use of the location and went so far as to move a number of scenes outside, "which, to my mind, just defied the whole premise of the story, which was, 'We can't go outside unless it's an absolute emergency,'" Masur admits. "After I saw the film, I thought John had made a good decision. So that big scene at night where where Kurt's going, 'I know I'm human' and burning the blood bags and everything. We [originally] shot that all inside in the rec room and it was a great scene — it was really tense and crazy. And then John, moved it outside and we're standing there in a line in the cold."

"Originally, he had me killed on the set indoors," Polis says of Fuchs, who carries forth Blair's research on the creature once the biologist snaps. "I've got a great picture of me hanging from the door with a shovel in my chest. He took a look at it and went, 'No, no — this isn't a slasher movie.' And so, he devised [this new death]. He actually gave me like five or six extra scenes when we went up to [Canada]. He wrote them for me, because I became the bridge to the science."

Another memorable sequence shot in the blistering cold of Canada was the death of Bennings, the first member of the group to be assimilated onscreen when he's briefly left alone in the storeroom with thawed-out alien remains. "If you see the movie and you see anybody with a beard like me, then you know that that person is not going to transform in the face. Because with with facial hair, it’s too difficult to make the [special effects] cast," Maloney explains. The creature barely gets to finish the absorption process when Windows returns, forcing the Thing masquerading as the meteorologist is forced to make a run for it. The monster doesn't get very far when it's burned to death by MacReady.

"I had no shirt on, my coat coat was wide open, and with the wind-chill, it was 103 degrees below zero," Maloney recalls, adding that the only source of warmth came from a pair of hand warmers stuck inside the false arms. "John said, 'Well, look, the cameras are going to maybe slow down here [because] it is so cold. I'm putting you in charge. If you feel that it's dangerous or it's too uncomfortable, you just tell me and we'll go back inside and warm up.' I don't remember asking him to do that. Actors want to please the director and sometimes, they can put their lives in danger because they want to do what the director wants. And we all want the movie to be terrific. We don't want to chicken out and deprive the movie of a scene that might be terribly thrilling to the audience."

The subsequent scene where Garry laments the death of his friend was the result of the aforementioned rehearsal process.

"I remember Donald saying, ‘Well, you know, Bennings is my friend. Why in the story do I not express my anguish at what we've just done to Bennings?’ Which was see this man overcome, the first one in our group, to shown signs of infection from this terrible virus," Maloney reveals. "Then we we kill him, we soak in with gasoline, we light a flare and we stand around and watch him burn, like a Tibetan monk protesting the war or something. It’s a horrific, horrific ending. Even though I’m half monster, half human, I plead not to be killed, with that strange bellow that comes out as me as I turned to look at Kurt before he throws the torch. Donald didn't know why his character was not expressing the human emotion that one would express if a good friend suddenly was killed ... And so, there was something written in there. Bill and John were very attentive, John especially, to what we needed."

Clennon expresses a similar sentiment about Carpenter: "If an ad-lib worked, he’d use it. He wasn't he wasn't real strict about sticking to the script."

For example, Palmer's "Thanks for thinking about it, though" line was not in the screenplay, but a suggestion from Clennon's friend, the late Don Calfa. "I say, 'I'll take you up there, to the Norwegian camp, Doc! I'll fly up there! And our captain, Garry, says, ‘Forget it, Palmer!’ Don Calfa said, ‘When he says that, try saying: Hey, thanks for thinking about it, though.’ He's a little out of touch and the captain, Garry just sternly, scornfully dismissed his idea. ‘Hey, thanks for thinking about it, though.’ Like, as if the guy had actually thought about it. And that line stayed in the it stayed in the film. It was ad-libbed and it was a gift from the late Don Calfa."

Another bit of improvisation can be found in the scene where Palmer and Childs get high and watch pre-recorded episodes of Let's Make a Deal. This brief, slice-of-life moment may seem irrelevant to the larger story, but it really hammers home the profound isolation and monotony these men face every single day. It just adds another layer of realism to the piece, wonderfully balancing the impending alien threat with concepts any human being can immediately understand. Palmer drives this idea home when he gets up to change the tape because he's already seen the episode currently playing on the television.

"I thought, ‘Look at the level of boredom that these guys have to contend with.' ... I thought, ‘Palmer, in his in his stoned orientation to the world, maybe sees these these game shows as dramatic structures.’ It's like you're watching a movie and you're stoned, you’re loving it, and you're watching this thing unfold before your eyes. It's a drama, they create this drama around a game — partly a game of chance and [partly] a game of guesswork. And so, he sees it in those in dramatic terms.’ And so, I thought, ‘I’m going to put one in the player and then I'm going to reject it, saying, Nah, I know how this one ends.’ I thought, ‘Well, that's a stoner approach to life. I don't want to watch this game show again because I remember how it ends. Give me a few months, maybe a few weeks, and I'll forget it [and] it'll all be new to me and I'll be surprised by the way by the way it plays out.'"

Cundey had the cameras "winterized," a process by which the manufacturer (in this case, Panavision) replaced the usual lubricant with an anti-freezing agent. "We [also] had a warming system for the the magazine on top of the camera that held all the film to keep the film from freezing and cracking and buckling. So keeping everything warm was an important thing." However, if the cameras were brought inside during breaks, the lenses would fog up with condensation from the temperature differential. "Pretty quickly, we decided that the room with the camera work always had to stay the same temperature as outside, below freezing. So the poor camera assistants never got a break to go into the warmth while they were working. They would go into the below-freezing camera room and they would work in their big parkas and their gloves and everything."

With regards to color, the cinematographer leaned into the idea of contrasts: "[For] the interior of the of the camp, I would tend to light it with a slightly warm light, implying that where they were living and working was kept warm compared to the exterior [which] tended to be blue. Sometimes, light coming from the camp would be warm so that we could say, ‘Oh yeah, that's warmth and safety over there' ... Blue tends to be something we associate with cold and freezing as opposed to warm light that we associate with fires and sunny days and all of that."

Tragedy nearly struck during a six-hour bus trip to Stewart, where the actors stayed for the duration of the real-world leg of principal photography. Everything was going smoothly until a white-out hit and threatened to send the bus off the side of a mountain. Proving himself worthy of the MacReady role, Kurt Russell immediately assumed control of the situation.

"Kurt goes, 'Okay, nobody move. Who's in the seat farthest from the door?' I said, 'I am.' He goes, 'Alright, Tommy — get on your hands and knees and crawl to the front,'" Waites remembers. "Slowly, I did it [and] I got off the bus. One at a time, he got us all off the bus. Then the weight shifted and we got behind the bus and we pushed it back on [the road]. And we drove [on] safely. This was before cellphones. There were no radios, no communications. We arrived at 5:30 a.m. as sun was coming up, and there was John Carpenter at the bus stop, waiting for his men. He shook each one of our hands as we got off the bus, not knowing the peril we had just been through."

"Kurt Russell was our captain," adds Maloney." He was hilarious and with us all the time. There was no separation of him and us the way there sometimes is with the star of a movie and the rest of the cast. We seemed to be all equals, except in the billing. At the end, of course, Kurt gets his [name] separately because he is the star."

In another instance, life imitated art with a bit of dissent amongst the ranks when Carpenter decided to cut a short exchange between Windows and Palmer. "It was sort of like a build-up to us fighting," Waites says. "But let's say it was three quarters of a page of dialogue. That's a lot of lines for an actor trying to get work."

He and Clennon had already gone over the scene together when it was suddenly axed. The two actors weren't very happy about this and spent the next 10 minutes or so verbally abusing their director — completely unaware that they were mic'd up. "John sticks his head around the corner [and] he goes, 'Hey, guys, I just heard every word you said.' And he wasn't laughing. It took me a while to dig myself out of that one. We were both mortified. And Clennon's like, 'Oh, come on, John! A little mutiny is perfectly normal on every set!' I think I wrote him a note to apologize, but I felt so terrible."

Clennon remembers the moment a little differently. According to him, the altercation was not over cut dialogue, but over the efficacy of trying to reinforce the outpost doors with two by fours shortly before MacReady — left for dead by Nauls — forces his way inside and threatens to blow up the whole complex.

"I said, ‘This would never work. This is this is silly. This is bullish**.’ And what I meant was in engineering terms, this ain’t gonna work. Any carpenter’s apprentice could tell you that what you're doing with these two by fours is not going to secure these doors. It's silly," Clennon says. "John had his headphones on and my mic was on. John came tearing across the set and started screaming at me, 'It is not bullsh**!’ He was just furious with me and I was I was kind of taken aback. I was shocked that I had been overheard and he didn't persuade me that I was wrong. But I figured, ‘Okay, well, we'll just try to fake it here and, and maybe nobody will notice.’ I think that was the case, I don't think anybody noticed that what we were doing was, at best, a fanciful way of preventing the monster from coming through the doors."

With that said, Clennon does touch on a number of early character moments that he wishes hadn't ended up on the cutting room floor. He points to the critical and box office success of Ridley Scott's Alien, which opened three years before The Thing, and followed a similar narrative about a collection of blue-collar workers battling a seemingly unstoppable beast from outer space.

"One of the things that made it work for me is that I got to know every single one of those characters. So when they were threatened, I knew who they were and I had a set of feelings about them," the actor says of the Xenomorph's big screen debut. "I thought that Bill succeeded in doing that. It was there on the page and it was there when we shot the film. When the film was released and I saw it for the first time, I thought that John had cut too much of the introductory material for each individual character ... I got lucky because he didn't cut a significant amount of my material. So by the eighth minute into the picture, you know who Palmer is. He’s an oddball, he's funny, he’s silly, and you kind of like him, so you don't want him to be absorbed by Thing."

Clennon claims one of the assistant editors gave him a heads up about this prior to the film's theatrical release. "She kind of warned me that John wanted to get to the first manifestation of the monster as quickly as he could. And so, he dispensed with a lot of the character stuff because he wanted to wow people with the monster. He was impatient; he was in a hurry to get there and he didn't want to linger over establishing a character."

"You Gotta Be F—ing Kidding..."

We'd be remiss if we didn't talk more about the most iconic scene in the film: the big reveal that Norris has been assimilated. "It definitely has to be when Dick Dysart gets his his arms bitten off. No one ever expected that," Waites says when asked about his favorite iteration of the creature. "The camera's underneath, from the patient's point-of-view, and he reaches in to see what's in there and he comes out with no arms. They got a real double amputee to play [Dysart in the wide shot]. I gasped."

"That had been storyboarded and when I do a film class, I show the storyboards as drawn and the actual images we shot. It's surprising how much they coordinate exactly," adds Cundey. "Because the storyboards were drawn very carefully to say, ‘Okay, here's the moment, here's the action we want to see, here’s the specific dramatic thing.’ I think that the fact that it was so carefully conceived was a big help. Having these storyboards and drawings of moments also gave Rob the inspiration to say, ‘Okay, the head has to stretch like this, and it has to crawl like this.’ And rather than just building stuff, he fitted all of the stuff into the moments that had been been conceived."

MacReady torches the Norris-Thing laid out on the operating table, but misses the head, which breaks away from the body and attempts to crawls off. Palmer catches sight of the arachnoid noggin and utters the piece of dialogue that perfectly sums up The Thing: "You gotta be f—ing kidding." It's a line that has echoed across the generations and inspired future filmmakers like Andy Muschietti who would go on to include a little homage to Norris's scuttling head in IT: Chapter Two.

"At some point, I think they came to the conclusion that this gag was going to be so spectacular — almost operatic. The ultimate Fourth of July fireworks display," Clennon explains. "It was gonna be so outrageous. The ideas that Rob Bottin was bringing to the table were just fantastic, and outrageous and unbelievable. I guess John and Bill came to the conclusion that the audience was going to be so blown away by this and they might even doubt what they had seen."

He continues: "There had to be some acknowledgement on the screen that what [the audience] had just seen was truly outrageous and spectacular. And somehow, they came up with, with that line. Maybe John or Bill just blurted it out. I'm imagining this scene where the guy's chest caves in and turns into a pair of jaws and snaps off the guy's arms and we go from there. So at the end of it, it’s like, ‘What do you say? We should say something because the audience is going to be reacting to this amazing display of gore and art.' It’s like, ‘Well, maybe we acknowledge that it's a little too much.’ So you say, 'You gotta be f—ing kidding' ... It’s like a humorous affirmation of what the audience is already thinking and feeling. And if they suspend their disbelief and buy the effects, it is truly horrifying. But it is also outlandish and outrageous and pushing the limits of credibility in a very realistic way. And so, you’re giving voice to what the audience is thinking. I think that's why that line is such a classic."

"One of my favorite scenes to shoot was [the one] after Charlie's head comes off," David says. "We’re following it [as] the head is crawling like a spider and David goes, ‘You gotta be f—ing kidding…’ That was some funny sh** … Clennon, he was just funny as hell."

"The first time I saw it, I just laughed my ass off," echoes Masur. "I thought it was so great."

"Now I'll Show You What I Already Know"

For the infamous and tension-filled blood test sequence, Cundey devised an ingenious system for hinting at the identity of the imposter:

"I took a certain liberty that when the guy we're most suspicious of is seen, I didn't put the eye light in his eyes. I didn't put that little sparkle that we use most of the time on characters to create the sense of life, of intelligence. I kept the light out of his eyes, so his eyes were the ones who were dark and dead. I think just subconsciously, the audience sensed that. It wasn't until years later that I said, ‘Okay, well, let me let me tell you what I did.’ And people said, ‘Oh yeah, now I notice.’ But it wasn't so much noticing as feeling, sensing, adding to the suspense. I think it paid off because it built that suspense as we went down the line from character-to-character and he was always lurking and waiting."

To achieve the effect of Palmer's blood running away after it's touched by the hot wire, the crew built a custom section of flooring attached to a gimbal that could move in any direction. "Then we attached the camera to the floor, so it stayed stationary, looking at this floor," Cundey explains. "No matter what direction we we moved the floor, the camera was always looking at the same spot. And then we put the blood on the floor and moved it around. As it would run in a particular direction, the camera would only see it as crossing the frame. I think it was pretty effective."

"I remember watching the behind-the-scenes process that you do to make the film moment work," admits David. "Where the blood was being come from and how it was going to look. The most remarkable thing was the hand and the petri dish. The hand is a mold of Kurt's hand, but it wasn't his [actual] hand."

"When you stick a needle in a human body, graphically in close-up, the audience is going to have reaction," Clennon says. "When you cut somebody's thumb with a scalpel, I'm going to have a major [visceral] reaction … So my theory is that a horror film director can use needles and scalpels, and fake blood to make an audience anxious and apprehensive and vulnerable to what's going to happen next ... having been softened up and made apprehensive and anxious and vulnerable, the effect of what you show them next — which is not real — is is going to enhance the effectiveness of the gag that you're springing on them."

Once exposed, Palmer starts to transform and ends up attacking poor Windows, who fails to burn the creature in time. "I believe I did my own stunts [for that]. They put me on some machine [and] that's me shaking around," adds Waites. "I think I did a few takes of it and then they said, 'Okay, let's do it with the stunt guy.' I seem to remember John letting me do it because I was in quite good physical shape at that time."

"I think maybe there were two or three grips, perhaps, just out of frame, who were shaking the sofa. I don't know if I was trying to amplify the shaking myself, I don't remember," Clennon says of Palmer's horrific convulsions just before the man's head splits open. "What strikes me about that scenes is that my face is expressionless. There's nothing going on with my face. I'm not grimacing or mugging for the camera. That’s a good thing, I think it's kind of striking that it's almost like Palmer’s not there anymore, it’s just his body that is vibrating as the Thing emerges. It’s almost like he's a corpse ... That's a very effective moment that the editors found and used to good effect."

For Clennon, the sequence works so well because Carpenter and Lancaster chose "the most unlikely character to be the Thing ... he is the least likely candidate. It can’t be Palmer, he's too flaky, he's silly, and he's harmless and he's funny. The Thing is not going to inhabit him! It's just not right. And lo and behold, that’s what you get ... I think it is a little shocking and I don't know if other people comment on that, but I don't think anybody's ready for it to be Palmer. There’s nothing sinister about Palmer and then all of a sudden, [it turns out] he fooled you."

The scene ends with one of the biggest laughs in the movie. Still tied up, a weary and beleaguered Moffat's Garry explodes at his comrades: "I know you gentlemen have been through a lot, but when you find the time, I'd rather not spend the rest of this winter TIED TO THIS F—ING COUCH!"

"He started out so calm and then he flipped out. We burst into laughter, it was really hard to keep it in," Waites remembers. "John's sets are really fun."

"Yeah, Well F*** You, Too!"

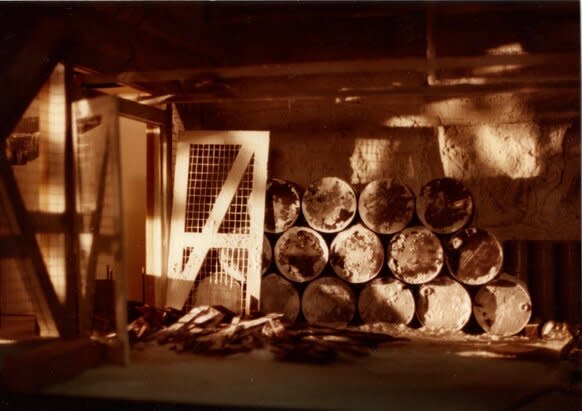

In addition to the UFO model that opens the movie, Frank also found herself tasked with creating a miniature version of the outpost generator room for the film’s explosive climax. “I went over and measured everything, took a big chunk of foam, cut it out, and figured out how to do all the different cans and that stuff,” she explains.

MacReady’s final standoff with the Blair-Thing was originally supposed to feature an extensive amount of stop-motion work by Randy Cook — only a fraction of which made it into the finished cut. “It was some great stuff," Carpenter says. "The creature comes up out of the floorboards and you see these tentacles. The problem is that everything we'd done was live-action [and] it just didn't fit. It just looked like a different movie and that was troublesome. So we just used the bared minimum.”

“Stop-motion at the time was still very stuttery and so, they decided to eliminate what had been designed in the storyboards and keep it down to one shot," echoes Cundey.

Multiple cameras were used to capture the total destruction of the camp once MacReady lobs the stick of dynamite at the Blair-Thing. "They blew up the set, which was gorgeous at night," Polis says.

"That was impressive," echoes Clennon, who was also present for the controlled demolition. "I believe that was the work of Roy Arbogast, who set the charges. He was the man was responsible for the destruction of the outpost, which was pretty thorough. That was a memorable moment for me. I thought it was worth sticking around. Generally, I'd be happy to go back to the hotel, but I stuck around for a while to watch that from a good distance. But that was very impressive and I think it shows on screen ... It’s a very good effect among many, many spectacular effects in in the movie."

The Thing (1982) Artwork Still Photo: copyright Susan Turner

The Much-Debated Ending

Even after all these years, fans still continue to debate the film's ambiguous ending. Was MacReady a Thing? Was Childs a Thing? Was neither of them the Thing? SYFY WIRE hoped to settle the discussion once and for all, but things (no pun intended) are rarely ever that simple. "I know who was the Thing in the end," Carpenter teases. "I know, but I'm not telling you ... I just feel like it's a secret that must be kept. The gods came down and swore me to secrecy."

"It was a beautiful night, it was cold, we had just finished watching all these explosions all around the camp," David says of filming that final encounter between Mac and Childs. "As I remember, there were five cameras all around filming from different angles. I remember sitting around, watching [mimics sound of explosions] and how exciting that was, before we had to do the scene. It was winding down to the last day, so there are all those mixed emotions in that among the actors."

With no concrete answers available, viewers have come up with numerous explanations. One of the most prominent theories out there posits that the bottle Mac hands Childs is not full of whiskey, but gasoline. The reasoning goes that if Childs was infected, he wouldn't be able to tell the difference, but that logic falls apart when you remember that the alien is capable of imitating its victims perfectly on a cellular level.

"We were both drinking out of the same bottle, so why would that be gasoline and [why would] he not be as dead as I would be?" asserts David. "Those kinds of comments, I don't even pay attention to them, because they're kind of stupid. [Mac] really is not Houdini, so where would he have switched the bottles if that were the case?"

"I appreciate them, but they don't know what the hell they're talking about," Carpenter says of all the fan theories. "There are some hilarious ones. Everybody says, 'Well, he took a drink, so he must be contaminated.' Blah, blah, blah. On and on. I'm not speaking about it anymore."

Others claim that Childs is a Thing because he has no eye-light in those final moments. Again, this does not hold up to scrutiny, as that system was only applied for the blood test sequence (Cundey himself confirms this). A third hypothesis alleges that Childs must be infected because you can't see his breath in the below-freezing temperatures. David, however, provides the perfect counter-argument to this:

"I don't know the last time that you were in the cold and standing by a fire [but] if you're in the cold, more than likely the wind is blowing. Whether it's blowing hard or blowing soft, the wind has a direction. If the wind is blowing in my direction, and the heat from the fire is coming at me, you're not gonna see the smoke come out of my mouth the same way as if someone on the other side of the fire, where it is cold, and the smoke is coming out of his mouth. So that theory didn't hold water for me either because if you've ever been by a campfire [in the cold], you know what that looks like."

"John never would reveal the answer or maybe never had an answer. He he just wanted to leave it hanging, so it would would be an intriguing ending," Cundey muses, revealing that there was plenty of speculation amongst the crew during the shoot.

"We came up with various endings as we were working. [One such] ending [had] Kurt [as] the only one left, a helicopter comes in because Kurt's going to escape and then somehow, the creature gets on the helicopter, and goes to the Navy ship and starts the sequel. Or should the two of them be rescued and then we find out that the other character is really the Thing and he escaped on this Navy ship? There were all kinds of stories written, mostly by the crew, as we sat shivering."

For Waites, the importance of the ending lies not in who might or might not be an imitation, but in how "no one trusts anyone anymore." Humanity's nasty habit of pointing fingers and making wild accusations is what makes The Thing so timeless (even more so than the '51 adaptation, whose obvious Red Scare allegory feels rather dated).

And while the '82 adaptation may have stood as a metaphor for the nascent AIDS crisis, its overarching message of eternal suspicion can be plugged into any time period and still feel shockingly relevant. "The idea that my standing next to you at a bar, I could get sick and die. You could be trying to overtake the species with your virus," Waites explains, drawing a parallel to the era of coronavirus. "That [John] had the prescience to know that our paranoia would just increase..."

"I think it means more if neither one of them is the Thing, and they're just gonna sit there until they freeze to death. It sure is bleak," adds Clennon. "I never resolved that in my own mind. I think the religion of American movies would not allow you to even entertain the idea that it was Kurt Russell because he's the star of the show and he brings the [whole] Kurt Russell thing to the movie, so it can’t be him. And I don't think it's Childs either. They're both right to be suspicious of each other. Given everything that we've seen, we know it’s possible that one of them is the Thing. But I also accept that they they have to be suspicious. It’s possible that the the Thing snatched Childs at some point and devoured him in six minutes and spit him back up again. But my personal take on it is that these neither of them is the Thing and they're gonna die in the ruins of that outpost.

An Ominous Opening

The Thing opened in theaters everywhere on June 25, 1982 — just two weeks after the release of E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (and on the same day as Blade Runner). By that point, moviegoers had already fallen head over heels for the squat cosmic visitor with a taste for Reese's Pieces, and didn't exactly know what to make of Carpenter's graphic and nihilistic slow-burn that The New York Times dubbed "instant junk." Even Christian Nyby, director of The Thing from Another World, publicly bashed the film.

"People liked the cuddly more than they liked the fear," Frank says. "It was softer. Ours was a little harsh compared to E.T. ... It was ahead of its time."

"It wasn't marketed," declares Polis. "They gave it two weeks of marketing. Cat People was supposed to open that weekend. They were so far behind on that and we finished up, the film was ready. They were gonna give us months of marketing and suddenly, they just shoved it into that position between E.T. and Poltergeist. E.T. was such a worldwide phenomenon, we just didn't have a chance."

"It was a disaster," Maloney adds. "No one came to see it. No one wanted to see it. They pulled it from the theaters ... Universal thought we were gonna save their ass. They were in terrible danger as a company and they had put their bets on John Carpenter's The Thing."

Produced on a modest budget of $15 million, the film brought in less than $20 million at the domestic box office, and Carpenter's career took a serious hit.

The last four decades have been unbelievably kind to the movie, which is finally considered (and rightly so) to be an unparalleled cinematic triumph, whose impact on pop culture cannot be understated. "I don't know if it's gone to masterpiece yet," says a humble Carpenter. "I know a lot of people have re-examined the film and have nice things to say about it now ... It's a lot like my work. It's kind of damned at first."

"It's unfortunate that The Thing didn't get the juice that it has gotten over these last 40 years," David says. "It's a film that really holds up well, and I think it's one of John's best. We had a kick-ass cast, it was a good story, there were so many wonderful things about it. But at the time that it came out, it did not get the accolades that it has consequently gotten over the years. That's the only thing I can say about it because it was wonderful working with John Carpenter. He's a wonderful filmmaker, and I wish he was still as active today because I would work with him anytime."

"Justice has prevailed," Waites proclaims. "I feel so vindicated, mostly for John. He risked his reputation on doing his movie his way, which is what a director is supposed to do. And because he did it, he suffered immediate backlash. But ultimately, 'The truth will out,' as Shakespeare would say. Whether you're a science fiction fan or a horror fan or just a cinema fan, you sit and watch it and you get pulled in by the music, by the cinematography, by the camera movement."

Maloney has witnessed profound cultural resonance firsthand at a number of fan conventions: "The movie means a lot to people. When you sit at a table signing autographs and three generations of a family come up dressed as cast members of The Thing...a grandfather, father and the grandson. They're standing there and ask you to say your lines that they remember [because] they've memorized your lines. They say, 'Say that line that we like!' And we do, and they have tears in their eyes."

"It's always a pleasant surprise to me to find out that people really have something to say about the film and about the larger world," Clennon explains. "I say that, even though I don't fully understand the the drawing power of the film. I don't fully get it … There must be something there because the people I'm engaging with are very bright, thoughtful people. So they're getting something out of this film. They see it and they take something away, and they go back to it again. They revisit it and that’s intriguing to me."

Credit: Universal Pictures

In Memoriam

While the intervening decades have brought about a great deal of deferred acclaim, they have also brought the unfortunate passing of several cast members: Charles Hallahan (1943-1997), Richard Dysart (1929-2015), Donald Moffat (1930-2018), and Wilford Brimley (1934-2020).

"[What] makes me sigh a little bit is how many of these guys aren't here anymore," Masur admits. "Dysart's gone, Moffat's gone, Charlie's gone, Wilford's gone. And then there are a few of us who are chasing up close behind them now."

The men may not live forever, but the close relationships they shared certainly will.

"You really couldn't wait to get to work every day — whether it was Wil Brimley doing rope tricks or Kurt telling stories ... whatever the day brought," Waites says. "Oftentimes, we would go out afterwards and get to know each other. [We'd] hang out and had a lot of laughs, man, a lot of fun. Under John's auspices, we forged a bond."

"We got pretty close," echoes Maloney. "As close as you can get, working together for six months on a movie [and] coming from all different backgrounds, different disciplines and training. I think about those guys and how wonderful it was to [work] with them and what a privilege it was to be in a movie with them. The human side of it."

Legacy From Another World

In 2011, Universal Pictures attempted to reboot the property with a prequel film (also titled The Thing), which depicted the events at the Norwegian camp and led directly into the events of the 1982 classic. Written by Eric Heisserer (Arrival) and directed by Matthijs van Heijningen Jr. (The Forgotten Battle), the project eerily repeated Hollywood history as a critical and box office misfire, with many audience members pointing to the fact that its unconvincing CGI did not hold a candle to Bottin's achievements.

As fate would have it, Cundey was "approached early on" to serve as director of photography on the prequel, "but they had already committed to somebody else," he reveals. "The fact that it was shot on a stage in a backlot with a lot of green screen — all the stuff that we we didn't do — was obviously more convenient and comfortable for them. The fact was they took a different approach and when I saw their film, I thought, 'Well, interesting, but it didn't have some of the same feel of the original.'"

"Even though ours is a remake, there was a good reason to remake it," Maloney explains. "Because when they made the [1951] original, they didn't have the technology to do what we did. They also didn't have the money to do what we did. And so, I excuse it on that level and say it's a totally different thing."

"I had plenty of chances to check it out and I never did. I was I was kind of curious about it. I feel like I should see it," Clennon concludes. "I understood two things about it and maybe maybe I'm wrong. [Firstly is] that the color palette that they used was very similar to the original Thing. The look of the film, the costumes, the colors, everything was very similar to the original. And then I heard a rumor that most of the special effects were practical, but that somebody higher up decided that they had to be CGI. That seemed like a terrible waste. Because I think I heard that the practical effects were quite good and there was no good reason to replace them with CGI."

If Carpenter had to choose a worthy successor to his movie, he'd probably go with the 2002 PlayStation 2 video game that picks up directly after the events of the '82 film. "That was fun, and I was in it," says the avid gamer, referring to the character of Dr. Sean Faraday, whose appearance was based on that of Carpenter, though it should be noted that the director did not record any dialogue. "It's a lot of fun and I'm happy to have my visage in it."

Funnily enough, the director's notorious love of video games was already apparent on the set of The Thing. "John used to play video games on the set in between takes and he would beat the machine every day," Waites recalls. "It was Pong, he would be playing it in between takes because it takes forever to set up [certain shots]."

Back in early 2020, it was reported that a new reboot — partially based on "lost" John W. Campbell Jr. material — had entered development. Appearing at the Fantasia film festival several that summer, Carpenter revealed that he and Blumhouse were directly involved with the project.

He refused to give up any details at the time and continues to stick to that caginess when we broach the subject. "Maybe…we'll see," he says. What the hell do I know? That's the theme of my career. Write [this] down... John Carpenter: 'What the hell do I know?' No one tells me anything." He also declined to speak hypothetically on the reboot when asked about what he'd like to see out of it. "I'm not gonna tell you that. That would be something I would figure out and do and then you would discover it in the movie theater."

The cast, on the other hand, is a different story. Polis would like to see "some great CGI" and a story that brings the property "up to date," especially in a post-COVID world. "If I had to do it over again, I would have been in a hazmat suit when we brought that Thing into the rec room — if we brought that thing into the rec room [at all]. I didn't watch it for years and when I saw it, I went, 'Whoa, we missed that.' Things like that bring it up into our [21st century] understanding of science and contagion."

David would like to see "a good movie — something that holds up and is worthy of the hype."

Maloney isn't big on the idea of reboots, but wishes the studio good fortune. "I hope they make money for themselves, but does it really interest me? No, I don't have any interest. They could fool me. They could say, 'Well, Peter, we've redone it. Bennings is dead, but we want you to be in it!' If they said that, I'd be happy to do it because of John."

Similarly, Masur doesn't see much value in rebooting a film "that worked really, really well. What you need to do is take something that didn't quite work, but should have. That's makes for a great remake, where it just misses or some piece of it doesn't come together or you do something where you flip it."

"I'd like to see John Carpenter's influence," Waites concludes. "I'd like to see them ask John to write the script or ask John to produce it or ask John to influence it in some way."

The Thing is now streaming on Peacock.