How Urban Retail Can Bounce Back from Theft Spikes

The retail industry might as well be walking around with two shopping bags of existential angst: one over thefts that threaten stores’ everyday bottom lines, the other over a lagging return of office workers to downtowns—which poses a longer-term business-model risk. But that doesn’t mean that you can chalk up every store closure to those trends—or even attribute any single shuttering to either rising theft, a subset of what retailers call “shrink,” or lower foot traffic.

“If a variety of factors, including shrink, are making a store unprofitable, then they’re going to close it,” says John Harmon, an analyst with Coresight Research. Emphasis on variety, he added: “Maybe the landlord raised the rent, or the location didn’t turn out to be so good.”

See, for example, Target announcing in September that it would close nine stores in New York City, Seattle, Portland and the Bay Area—while its list of 35 upcoming stores (as of late October) includes multiple urban locales, five in New York alone. And depictions of retail decline as a “doom loop” cycle for city centers should be viewed in the context of earlier forecasts that got negated by reality.

“This fear is not new, nor is it destiny,” wrote Tracy Hadden Loh and Hanna Love in a March 2023 paper for the Brookings Institution, in which they recount over three decades of city centers seen as “dangerous and declining,” then “increasingly unaffordable and exclusive,” and now “being ‘dead’ once again.”

Not the Theft As Much As the Threat

The theft picture can look bad enough both up close–when barren shelves greet you in a store–and seen in media headlines covering developments like major retailers fleeing downtown San Francisco in response to sometimes violent robberies.

It can seem less awful, however, in the big-picture perspective provided by the National Retail Federation’s 2023 Retail Security Survey, prepared with the Loss Prevention Research Council. The overall figures there show that shrink, as calculated by retailers who responded to the survey, hasn’t changed that much over recent years. As the report says on page one, the average shrink rate in fiscal year 2022 increased to 1.6%, up from 1.4% in FY 2021 and in line with shrink rates from 2020 and 2019.

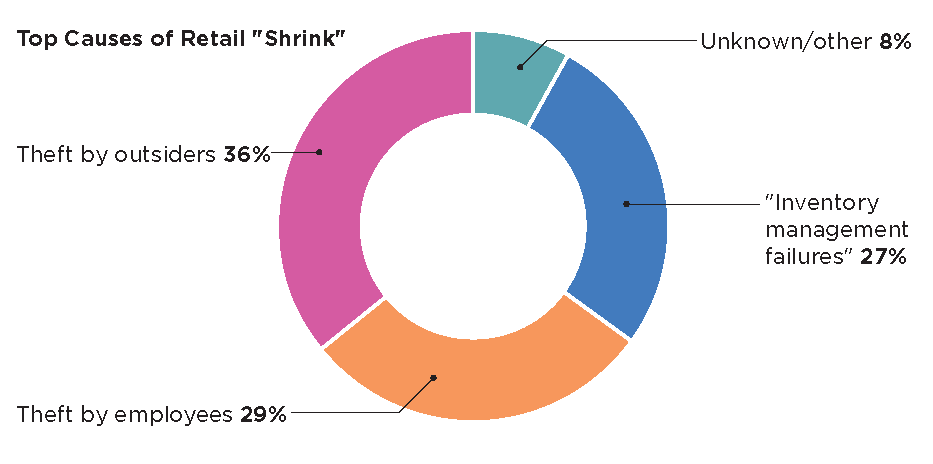

And most of that $112.1 billion in FY 2022 loss didn’t involve shoplifting of any sort: While theft by outsiders added up to 36%, thefts by employees accounted for 29%, and unspecified inventory-management failures comprised 27%, with the balance going to “unknown” and “other.”

But NRF’s survey also captures the fear of retailers scared of violent theft, with 88% saying that thieves are “somewhat more or much more aggressive and violent compared with one year ago.” (think of the well-publicized smash-and-grab robberies

that have plagued high-end shops around San Francisco’s Union Square.) And retailers who said they were specifically tracking violent theft attempts said they had seen those increase by 35%.

Coresight’s Harmon said that explains why retailers often tell employees not to disrupt shoplifting attempts in progress: “It’s not fair to ask them.”

Respondents said much of the theft problem involves organized retail crime (“ORC” for short) orchestrated to snatch products for illegal resale in places that can range from sidewalk markets to an eBay storefront. But the NRF report did not put numbers on the scope of the ORC problem.

Some skeptics have pointed to police-department statistics to suggest that retail chains are latching onto theft in a blamestorming exercise to justify closing stores that don’t pencil out for other reasons. For example, journalist Judd Legum looked at crime stats near to-be-closed Target stores in Seattle and San Francisco and concluded in his Popular Information newsletter, “This data suggests that factors other than crime are driving Target’s decisions.”

Harmon, however, warns against taking those comparisons too far: “A lot of these thefts are just not reported.”

A July 2023 report by Seattle’s city auditor backs that up, noting that the Seattle Police Department said it received zero theft reports in the first quarter of 2023 from unspecified “large downtown retailers” that had brought on more of their own security guards and for unstated reasons elected not to file reports to the department.

That report also underscores the importance of police work to break up ORC rings, citing 2019 efforts by Auburn, Wash., police to prosecute suspects behind thefts of an estimated $18 million worth of goods. The work paid off for local retailers, which the report said later “reported at least a 30 percent drop in ORC.”

Countermeasures, One Store Counter At A Time

The NRF survey found that closing stores was a third-place remedy, with about 28% of respondents saying they had shuttered some locations versus 45% saying they had reduced the opening hours of some stores. About 30% reported that they had “reduced or altered” their on-the-shelf inventory.

That last change is hard for shoppers to miss when they see retailers locking up some products or dropping others. For example, Giant Food recently removed national brands from one theft-prone location in Washington, D.C., leaving only in-store brands instead of closing its sole store east of the Anacostia River in one of the District’s poorer and most majority-Black neighborhoods.

Coresight’s Harmon put in a plug for less-obvious countermeasures. Increased use of computer-assisted video surveillance can help a store spot patterns of loitering that could be a prelude to shoplifting. “Often, if an associate walks up to a would-be shoplifter and asks, ‘Can I help you?’, they lose their nerve,” he says.

Cameras set up above self-check-out stations can also remind shoppers that they’re being watched. For example, while Walmart has closed self-check lanes at three Albuquerque, N.M., locations, it runs machine-vision-powered cameras above self-check stations at more than 1000 stores.

Amazon takes that idea to a logical extreme with the “Just Walk Out” automatic billing that its Amazon Fresh stores and some third-party retailers now employ. You scan a credit card or digital ID on entering, cameras and sensors log everything you put in your cart, and you’re automatically charged for whatever you walk out with. Stealing essentially becomes impossible.

But Harmon is much more bullish on a form of in-store tracking that operates even when individual products sit on shelves. Cheap radio-frequency-identification (RFID) stickers can function without a battery, be read by cheap hardware, and allow real-time tracking of products, whether they’re moved by staff or a shoplifter.

Retailers can also employ these tags as a direct theft countermeasure: Lowe’s is working with power-tool manufacturers to have them embed RFID tags in their hardware to render these tools inoperative until an RFID scanner at a checkout counter unlocks them. This “Project Unlock” initiative also envisages having that scan write an anonymized record of the transaction to a public blockchain to provide subsequent verification of a legitimate purchase.

Fewer Neighbors, More Problems

Business districts that have fewer people around represent a different problem for retailers. More than two and a half years after the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines and the subsequent drop in severe infections, office occupancy in the top 10 markets remains stuck at around 50%, according to weekly reports from the building-security firm Kastle.

“Does it take a bite of retail? Yes it does,” says Sharon Woods, owner and founder of

LandUseUSA Urban Strategies, a real-estate development consultancy in Laingsburg, Mich.

“Routine-based purchases get hit pretty hard by a lack of commuter traffic,” says Owen Riley, another analyst at Coresight. He points to groceries and convenience stores as the most common casualties of this trend, although he adds that smaller cities below Kastle’s top 10 are seeing a stronger return to office. And flexible return-to-work schedules may not do retailers many favors.

“They’re there on Tuesday, they’re not there on Wednesday,” Riley says. “It’s tough to build any sort of a routine around that, and that includes shopping.”

Cities tiring of hoping for a resurgence of traditional commuting patterns are increasingly leaning into converting older, less valuable office buildings to residential use. Washington, D.C., for example, now features multiple such projects under way on downtown streets that were once unbroken stretches of office space.

But the large areas between exterior walls in many office buildings, plus such other possible building-infrastructure wrinkles as plumbing and electrical work, can complicate conversion projects.

Says Woods: “It’s not cheap. It’s not as easy as it looks.”

American-style zoning has traditionally emphasized functional segregation of neighborhoods—so obvious you can see them from 35,000 feet up. Offices go here, homes go there, shops belong at intersections in between.

Riley suggests that the past few years of having home and work “all just muddled together” have shown that it’s time to drop that school of zoning thought.

“It probably means that the future is not separating things out as we used to,” he says. “Siloing things doesn’t look like it’s coming back.”

Source: National Retail Federation

Mixed-Use From the Start

One of Washington’s newest neighborhoods illustrates how mixing and matching office and residential development can yield a more resilient local market.

NoMa—the name abbreviates “North of Massachusetts Avenue,” a traditional boundary between that neighborhood and Capitol Hill—has steadily grown upwards since the 2004 opening of a station added between existing stops on the Red Line of Washington’s Metro mass transit.

But this growth has happened without tilting too much towards office or residential—and with space set aside for ground-floor retail in these new structures.

“We have apartments, we have office space, we have hotels, and we have lots of retail,” says Maura Brophy, NoMa Business Improvement District president. “We’ve had much more retail open than close since the start of the pandemic.”

That’s not because the neighborhood doesn’t have office spaces vacant for a chunk of the week.

“We do experience the ongoing effects of remote work when it comes to less activity in the neighborhood,” she allows. But having residential mixed in does dampen those effects: “Whether there’s someone working in an office or working from home, there are people working in NoMa.”

The BID uses Placer.ai’s location-analytics software to track pedestrian activity through people’s smartphones; that data shows pedestrian counts approaching 60% of pre-pandemic levels, Brophy says.

The area also benefits from two high-profile examples of destination retail: a flagship REI store built in the shell of the since-dilapidated arena that hosted the Beatles’ first U.S. concert in 1964, and the Union Market food hall (which itself used to be much less shiny) and the cluster of shops and growing around it.

Woods endorses having unique places like that to provide experiences that people can’t get by shopping online or driving to shopping districts hosting the same Anyplace, U.S.A., establishments.

“The downtowns that are going to succeed are the ones that offer ways for patrons to feel socially connected,” she says. “The downtowns that are thriving right now are managing to knit together some discovery-type retail.”

Brophy credits NoMa developers, retailers, and residents for fueling this symbiotic relationship. As she says: “They’re proving this hypothesis that mixed-use neighborhoods are the post-pandemic neighborhood of choice.”