Why Big Pharma can’t quit the lab monkey business

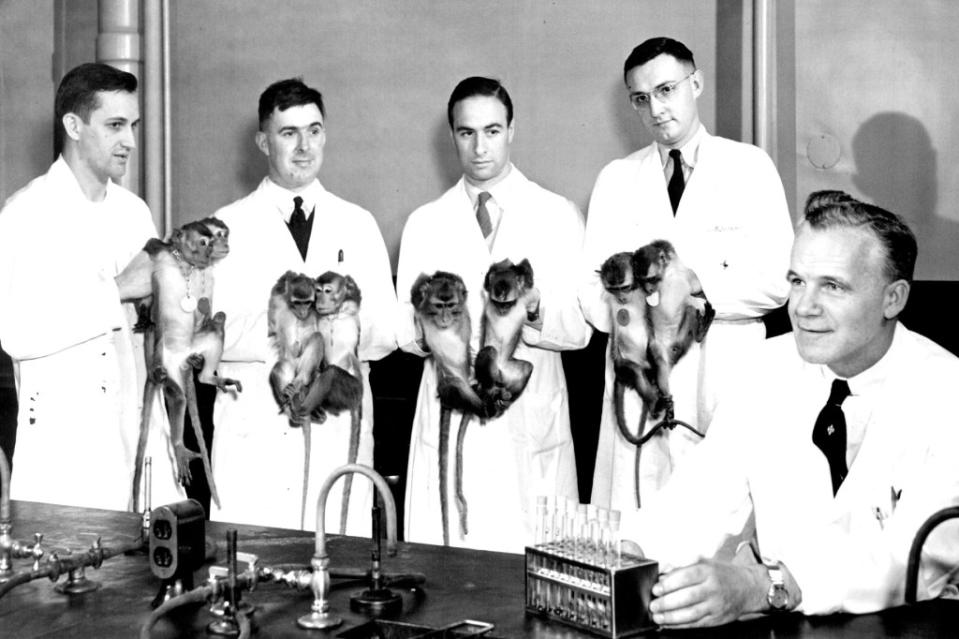

Can Big Pharma produce the medicines and treatments America needs without the long-tailed macaque?

It's not a rhetorical question. The go-to lab monkey for the $586 billion biopharmaceutical industry and many areas of research is at the center of the complicated international trade drama that industry groups say threatens to clog the nation’s vital drug development pipeline.

Twice in recent years, the research community has experienced sudden, serious shocks to its monkey supply: In 2020, at the beginning of the Covid pandemic, China stopped exporting its captive-bred long-tailed macaques, cutting off the US drug industry’s main source. American importers pivoted quickly to monkey breeders in Cambodia, which supplied the U.S. with 60% of those brought into the country between 2020-2022. But for more than a year, the U.S. government has effectively stopped the import of all Cambodian monkeys, as part of a crackdown on alleged smuggling of wild-caught monkeys into the pipeline of captive-bred research animals. (Read my Fortune feature on this here.)

The whole mess leaves the industry, which relies on the animal for required safety and efficacy testing, in a real jam—and scrambling to find solutions to this debacle, from resuming Cambodian imports to increasing domestic breeding.

But are more macaques really the answer? The whole affair has brought unwelcome attention to an unpleasant, inescapable truth hidden within the triumphant narrative of scientific progress: that our success curing and treating all kinds of human diseases and conditions depends on this precarious trade—and on sacrificing the thousands of monkeys that travel through it. Inflicting harm and death upon animals for the sake of science is a practice that more than half, 52%, of Americans oppose, according to a 2018 survey by Pew Research Center.

In a world of fast-advancing technology and precision medicine, does it really have to be this way? Are live monkeys—our primate relatives—really the best tool for developing and testing human medicines?

A fraught business

Certainly animal rights organizations, which oppose all such research on moral grounds, argue it’s time to switch to non-animal alternatives now. In support of their argument, activists often dismiss the scientific value of animal research, point to weak regulation and enforcement of animal welfare laws, and raise the threat that the animal trade poses to public health. They also have called for the long-tailed macaque to be declared endangered in the U.S. to protect the species and stop its trade. (Read more about the thorny question of whether the long-tailed macaque is endangered here.)

The scientific community shares the long-term vision to quit animals in research, but contends that’s simply not possible yet—no viable alternative currently exists to fully test the safety and efficacy of drugs. In the meantime, researchers and industry folk resent activist groups’ efforts to undermine that work. The long-running, international “Gateway to Hell” campaign, targeting companies that transport lab animals, has been so successful that no major airlines will fly monkeys, for example.

“They have driven up the cost of transporting animals, which is exactly what they intended to do,” says John Sancenito, President of Information Network Associates, a risk management and security consulting firm that works for the industry. “They wanted to make it more expensive, they wanted to make it more difficult for the industry to move animals from country to country.”

The use of our highly intelligent primate relatives has always been especially contentious, and the lines in the highly charged debate are often crudely drawn. In the ferocious rhetoric of pro- or anti-animal testing partisans, animal researchers are either craven monkey torturers running frivolous experiments or unimpeachable practitioners of life-changing science.

The truth lies somewhere in the middle. As the research community likes to point out, scientists are bound by regulation and committed in principle to using animals responsibly and only when necessary. Decades ago, the field embraced the “3R’s”—reduce, refine, replace—an industry-wide mantra of continual improvement in terms of animal welfare standards and reducing the cost in terms of animal lives over time.

Regulators are working on it too. A U.S. Food and Drug Association spokesperson told Fortune in an emailed statement that the agency “is committed to doing all that in can to reduce reliance on animal studies.” The agency opened the door for pharmaceutical companies to use non-animal alternative methods in the safety testing required for FDA approvals several years ago. And promising technology, including AI and organs-a chip—miniature systems that mimic the properties of specific human tissues and organs—are advancing quickly and helping reduce the number of animals used in studies.

But for now, the statement added, live animal subjects, including nonhuman primates, are still needed, as “alternative testing methods are, at present, often not capable of adequately assessing human risk of drugs.”

Safety first

When it comes to drug safety studies, the stakes are very high, say industry representatives. By using live animal models, “We are keeping people safe from bad drugs.” says Steven Bulera, chief scientific officer for safety assessment at Charles River Laboratories, one of the nation’s leading contract research organizations. (Pharmaceutical companies outsource much of their preclinical work, including safety and efficacy testing using lab animals, to such companies.)

And the system works to weed out dangers, Bulera claims: Roughly 60% of the compounds Charles River tests in animals are dropped from development due to toxicities discovered in animal trials. He adds that the company is already using new technologies to eliminate dangerous drugs before they reach animal studies, but they can’t yet fully model the impact of a drug on a complex, multi-organ human.

"We’re in the infancy of this,” says Bulera, who estimates it’ll take decades to get to the point where live animals aren’t necessary. To demonstrate the complexity of the task, he explains that with for monkey studies, his team typically monitors numerous endpoints including the animal’s heart rate, body temperature and 65 different tissues to assess the safety of the new drug.

Researchers swear they don’t like to use monkeys for this work. And moral questions aside, the animals are incredibly expensive and difficult to use for reasons of logistics, temperament, and disease risk. If there were another animal model or alternative technology that suited the work as well, they’d use them, they say.

Traditionally, companies have used two animal models—one small, like rodents and one large, like a long-tailed macaque—to study drugs before they enter human trials. What drives the decision, says Bulera, is science. “What you’re trying to do is to pick the species that best represents humans from a metabolism point of view, from an absorption point of view,” he explains. “There are drugs that might get absorbed better in a dog than a monkey, they may get better absorbed in a minipig.”

Each species used in animal research tends to have their own well-honed use cases: pigs are highly sought out for dermatological studies, for example, while dogs are a preferred model for cardiovascular research.

When it comes to testing biopharmaceuticals, the fast-growing class of drugs that include monoclonal antibodies, long-tailed macaques (usually called cynomolgus monkeys or simply NHPs in lab settings), which share more than 90% of our genetic material with humans, are favored. Without the long-tailed macaque, says the National Association of Biomedical Research, 53% of the 19,742 drugs and biologics currently in development “may never make it to market.” The same goes for 57% of the 7,439 oncology drugs and biologics currently in development. Six of the nation’s top 25 prescription drugs—used to treat pain, depression, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure—involved long-tailed macaques in their development.

And the case for using a particular animal grows stronger with time and experience: As data accumulates, the model becomes better characterized, which gives confidence to researchers and regulators making decisions based on it.

The limits of animal models

But are animal studies good science? How useful is all this animal data to understanding human disease and drug reactions in people?

After all, as Rick Bright, former director of the Biomedical Advanced R&D Authority or the federal agency known as BARDA likes to say, “Humans are not mice, rats, ferrets, dogs, or monkeys.” He laments what he sees as the field’s continued overreliance on animal models in drug development. Time after time, he says, they’ve proven too inexact to be useful—with drugs and vaccines that work in animals failing in people.

Indeed, the limitations of animal research are real and often consequential. Unappreciated differences between species have tripped up scientists throughout history. Consider the polio vaccine race, where the rhesus macaque was both an undeniable asset to the scientific process—it was one of the first animals discovered to develop the disease when injected with the virus—and a drag to it. For years, scientists didn’t realize that macaques, unlike humans, were not orally susceptible to the virus, a misapprehension that for a long time threw off their understanding of the disease’s pathway and confounded efforts.

The same issue lies at the heart of the field’s ongoing “reproducibility crisis,” the shattering reality that roughly half of animal studies can’t be replicated. The scandalous ignorance of researchers is often to blame, says Joe Garner, a professor of comparative medicine at Stanford and an animal researcher himself. Among problems he has cataloged: scientists mistaking common glands for tumors in mice, and failing to consider the impact of animal stress or other welfare lapses—caused by environment, noise, or other stimuli—on study results.

The costs of flawed methods—the many drugs that work in animals but fail to translate to results in humans—are staggering, he says.

The research community’s bitter dynamic with activists often stymies honest, productive conversation within the industry about these real issues. “They’re so afraid of giving additional ammunition to animal rights groups,” says Bright, who argues the industry should be using far fewer animals. (Bright began his career at a national primate center where he remembers his car being pelted with rocks and tomatoes as he arrived at work.)

As many in the scientific community advocate to expand the U.S. breeding of nonhuman primates for research, Bright dismisses the idea as strategic folly. All investment, he argues, ought to go towards accelerating development of and regulatory pathways for alternatives that can produce more human-relevant science.

“Not only can we replace a lot of the animals that we use, we could do a much better job," he says. "We can get lifesaving medicines through the development pathway much sooner.”

He points to emerging technologies that would allow researchers to test drugs in synthetic systems that reflect the breadth and diversity of the whole human population, an approach far superior to testing compounds in a population of captive-bred monkeys (which he adds tend to be inbred populations that are predominantly male).

A long road ahead

The FDA, the Institutes of Health, and many companies, like Charles River, are all investing in new testing methods, but Bright argues more urgency is required. Even then, the transition won’t be easy.

Business models and institutional cultures built around animal studies have proven hard to change, in part because the pharmaceutical industry is inherently conservative. On average, it takes over a decade and $2.3 billion for a pharmaceutical company to develop a new medication, an expensive slog that few companies want to risk tinkering with. Introducing a new non-animal safety testing method into the process is an expensive gamble that requires validating a new technology and working through issues with regulators. Few drugmakers want to be the industry test case, so sticking with a conventional monkey study is the easy way to go.

“Even though there are challenges with doing everything in an animal model…that is what the FDA knows,” says Bright. “Most of these alternatives are pretty new and so there’s not a lot of data behind them.” He expects for the next few years, companies leading the charge will have to do studies in parallel—using both animals and alternative methods—to prove out the technology and provide a bridge between data sets. It will take time, but he’s bullish about the potential of these approaches over the next decade to deliver better drugs, faster and without the loss of so many animal lives in the process.

In the meantime, the scientific community should adopt a more ethical approach when in does animal research, says David DeGrazia, a professor of philosophy and George Washington University. That means reckoning with the field’s shortcomings, and the fact that many animal study results don’t translate to humans, and asking, all things considered (including animal harm), will this research genuinely benefit the public? In 2019, he co-authored a new ethical framework for the field, hoping to move it beyond the “3Rs,” which he says has proven woefully insufficient in ensuring responsible animal research.

The scientific community could also benefit by listening to its critics, he adds. “They might say, the public isn't educated about the science, they don't understand what's at stake… but the scientists aren't educated about moral status, and they're not deeply educated about ethics,” he says. “What the public thinks does matter.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com