Repo markets and the liquidity crunch: Yahoo U

In mid-September the oft-overlooked underpinnings of the U.S. financial system became one of the biggest stories as the repurchase agreement (or repo) market faced a bizarre liquidity crunch.

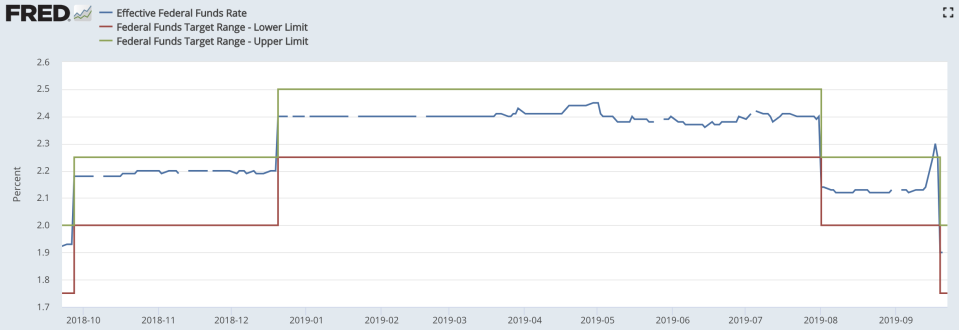

Overnight on Sept. 16 and 17, rates on overnight borrowings of cash spiked as high as 10% for some dealers, about four times the target range of where the Federal Reserve would like interest rates to be.

The New York Fed reacted to the spiking costs by offering a repo facility of its own, the first time it has offered a substantially-sized program since 2008. Each morning since the liquidity scare, the Fed has made available $75 billion of repo offerings and announced Sept. 20 that it would be opening three additional 14-day operations of $30 billion each.

The move provided some liquidity to a market hungry for bank reserves.

On Sept. 23 New York Fed President John Williams said the operations appear to have worked as expected.

“We were prepared for such an event, acted quickly and appropriately, and our actions were successful,” Williams said in prepared remarks at a conference in New York.

But concerns still exist about whether the Federal Reserve balance sheet left enough bank reserves in the systems to avoid future episodes of squeezed liquidity.

For even experienced financial professionals, the above may sound like a foreign language.

So what exactly is the repo market, how does it involve the Federal Reserve, and why did the Fed need to intervene?

What is repo?

The repo market is considered to be the “plumbing” of the financial system since it provides overnight financing for the banks and broker-dealers at the center of the economy.

Financial firms have substantial portfolios of securities that need to be financed with cash. Depending on where their holdings are by the end of the day, they will borrow cash overnight to fund those securities.

Repurchase agreements are a way to get this cash; at night one bank will lend funds to another bank, which puts up some of their securities (like U.S. Treasuries) as collateral to support the transaction. Then, in the morning, the borrowing bank will repay the lending bank with interest and reclaim the securities put up as collateral.

This does not mean banks are insolvent or lack the cash for consumer deposits; it is instead a way for banks to meet their day-to-day payments based on the securities they hold.

So how liquid is the repo market?

Because repo markets rely on cash held by other dealers, the liquidity of the market is based on the amount of bank reserves available in the system.

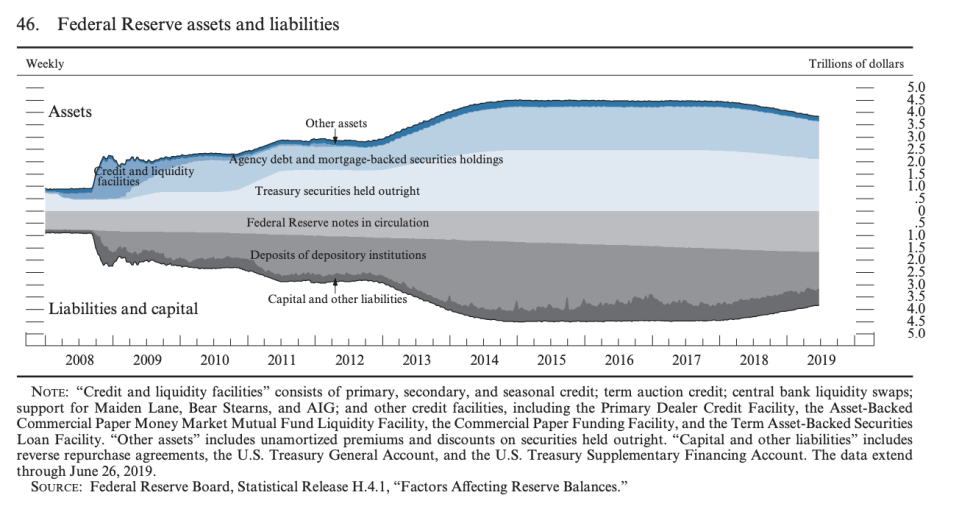

Over the last three years, bank reserves (in excess of funds required for regulatory purposes) have declined as the Federal Reserve shrunk its balance sheet in a process called “quantitative tightening.” Since 2017, the Fed has tried to unwind its large holdings of assets that it accumulated to battle the financial crisis. Bank reserves are the Fed’s liabilities against these assets, meaning the decrease of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities were being matched with contracting deposits in the financial system.

The Fed stopped unwinding its balance sheet August 1.

As a result, banks have had fewer reserves available to lend one another. Until mid-September, the reserves appeared sufficient enough for the short-term borrowing needs of the system. But with corporate tax payments and Treasury auctions needing funding in September, the rush for a reduced amount of bank reserves sent overnight borrowing rates higher.

The effective interest rate being paid in the markets spiked up to 2.3% on Sept. 17.

So how does the Fed work itself into this?

At 2.3%, interest rates were above its target federal funds rate range of between 2% to 2.25%.

Whenever the Fed makes an interest rate announcement, the Fed does not magically move rates on its own accord. The target is aspirational, and the central bank steers rates into its target range by paying interest on reserves.

As the bankers’ bank, the Fed pays interest on reserves that banks leave at the Fed overnight. So if the Fed would like interest rates in the target range of 2% to 2.25%, it will pay something in the middle of that range to set a benchmark at which banks will hopefully lend to one another.

The Fed refers to this operating structure as a “floor” system, since banks tend to then lend overnight funds to other banks in the private market at that same interest rate or slightly higher.

When the effective interest rate spiked about the high end of the Fed’s 2.25% range, questions arose over whether the Fed had lost control of its interest rates.

Okay so what did the New York Fed do?

On the morning of Sept. 17, the New York Fed dusted the cobwebs off of a book it hadn’t used since 2008: a large operation of its own repos that it would offer to primary dealers. As an extension of repos available in the private market, the Fed hoped a flood of another $75 billion of agreements would alleviate pricing pressures on rates.

The Fed has since made its $75 billion repo facility available once each morning (meaning that the Fed isn’t “pumping” a new $75 billion each day, but rather recycling the same $75 billion as new overnight repos, daily). On Sept. 20, the Fed announced it would also offer three $30 billion operations of 14-day repo operations through mid-October.

Is the Fed planning on doing anything else?

In Washington, D.C., the Fed Board attempted to rein in the effective interest rate by coupling its 25 basis point cut on Sept. 18 with a 30 basis point cut on interest paid on reserves to set a lower floor. By the day after, the effective interest rate fell to 1.90%, comfortably in the newly lowered target range of 1.75% to 2%.

The Fed is now weighing other tools to ensure that interest rates are under control, such as resuming “organic” balance sheet growth to increase bank reserves in the system. Policymakers are also exploring a “standing repo facility” that would allow banks to convert Treasuries to reserves on demand (instead of at pre-set times each day, as is currently the case).

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said Sept. 18 that the central bank is well-equipped to deal with future episodes.

“If we experience another episode of pressures in money markets, we have the tools to address those pressures,” Powell said. “We will not hesitate to use them.”

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the banking industry and the intersection of finance and policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

Boston Fed’s Rosengren: Lower rates could expose co-working companies like WeWork

St. Louis Fed's Bullard: 'Prudent risk management' would have been a 50 basis point cut

Powell faces record dissent as Fed splits further on interest rates

‘The weirdest place in the world’: What the Fed missed in Jackson Hole

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance